Editor’s note: This story is part of a special section on the 100th anniversary of Mazda to be published in the Jan. 27 print edition of Automotive News.

In the mid-1960s, Japanese goods such as motorcycles, cameras, watches and consumer electronics were starting to shed their post-World War II era image for shoddy quality. American consumers were finding many Japanese products to be innovative, cleverly designed, attractive, reliable and affordable. But it would take longer for Japanese automobiles to gain traction outside of Japan.

In 1961, Toyota suffered the public embarrassment of having to withdraw its Toyopet brand of cars from the Unites States after the Crown and Tiara sedans failed. Nissan barely had a toehold in the United States, selling a few hundred Datsun-brand pickups and sports cars a year. Tsuneji Matsuda, president of Toyo Kogyo — Mazda’s original corporate name — knew his tiny company stood a better chance of competing in global markets if it had technology that was not only different from its competitors, but also very innovative. That’s when Matsuda turned to the rotary engine.

Invented by German engineer Felix Wankel in West Germany, the rotary engine attracted attention from a number of automakers. Instead of pistons moving up and down in bores, the rotary engine used triangular-shaped rotors on an eccentric geared shaft mounted in an oval-shaped (called epitrochoid) case. It was a compact, lightweight and high-revving engine.

Because the rotors turned in one direction, the engine was exceptionally smooth.

It was beset by difficult technical problems, but Matsuda felt that if his engineers could solve the reliability issues, improve the fuel economy and clean up the engine’s emissions, the small, fast-revving rotary engine could be the technology to kick-start the Mazda brand around the world.

In assigning 47 of the company’s top engineers to work on the rotary engine, Matsuda gambled a considerable amount of Toyo Kogyo’s limited resources on perfecting an unproven technology. In a company history, Mazda says that the 47 engineers in the company’s Rotary Engine Research Department initially struggled to solve the problem of the seals on the tips of each rotor scoring the chrome-plated surface of the epitrochoid case.

Criticism of the project mounted inside the company and some decried it as a waste of money. But Kenichi Yamamoto, head of the research department, told his engineers: “From now on, the rotary engine must be on your minds at all times, whether you are sleeping or awake.”

Finally, in 1963, engineers tried a new design for the apex seal that solved the scoring problem.

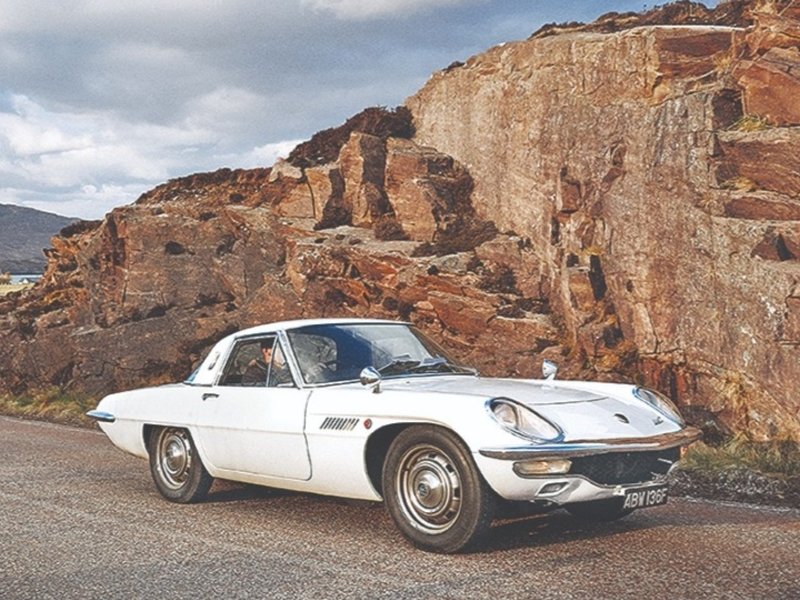

The next year at the Tokyo Olympics, Mazda showed a prototype of the stunning Cosmo Sport, a futuristic coupe designed specifically for the rotary engine. Three years later, production of the engine and the Cosmo began.

Mazda then used the rotary engine in a variety of small cars, and even in a compact pickup.

But it wasn’t until 1978 that the rotary engine was embraced in a big way. The RX-7 sports car was exactly the high-volume hit Mazda was looking for. The wedge-shaped two-seater weighed less, ran smoother and revved higher than its main competitors from Japan, the Nissan 280Z and the Toyota Supra, and it boasted higher quality than the aging sports cars from Great Britain, the Triumph TR7 and TR8 and the MGB.

Others had attempted the rotary concept and given up, including General Motors, Germany’s NSU and France’s Citroen. NSU built the stylish Ro 80 coupe, but its rotary engine suffered mechanical failures that sullied the brand. Citroen produced the GS Birotor for one year, 1974, but sold only 847 cars. GM came close to producing its version of the rotary engine in the mid-’70s for use in performance versions of the Chevrolet Vega and Monza. GM engineers were able to solve the engine’s technical problems, but escalating gasoline prices and tightening emissions standards led GM to cancel the introduction scheduled for the 1975 model year.

Mazda kept improving the rotary engine until it went out of production in 2012. There were technical issues over the years — some serious. But the engine retained its loyal following. And Mazda hints that the rotary may return, perhaps in a gasoline-electric hybrid.

Don Sherman, former editor of Car and Driver, bought an RX-7 new in 1979 and still has it. He believes the rotary engine’s best chance of seeing production again is in a range-extended hybrid that uses the fast-spinning rotary to power a generator that produces electricity for the car’s drive motor. But he’s not hopeful.

“The output shaft is in the middle of the engine, just like an electric motor. And the rotary is sort of shaped like an electric motor. They are compact and they are smooth, so it makes physical sense,” Sherman said of the rotary engine.

“You could operate it at a fixed rpm, and you could optimize all its design parameters to suit a range extender. But that’s about it.

“There’s still carbon that comes out the [exhaust] pipe, and Mazda doesn’t really have the resources to seriously address the issues.”

Lately, Mazda has been focusing its powertrain engineering budget on developing the high-compression Skyactiv-X engine, which once again aims to separate Mazda from its competitors with a small, powerful engine that expands the boundaries of combustion technology. Only this time, Mazda is using pistons, not rotors.