OTTAWA LAKE, Mich. — Among automakers that prioritize safe testing on the promising road toward fully automated driving, Toyota is out standing in its field.

Or rather, driving out there, while simultaneously simulating one of the most densely packed areas of Tokyo in the middle of a field in southeastern Michigan and under the shadow of a set of 115-foot-tall grain silos.

Does that seem corny? Well, not anymore; this year’s surrounding acres of corn have been harvested. Yet the work goes on at the Toyota Research Institute’s Automated Vehicle Test Facility on the Michigan-Ohio border, where the automaker is trying to achieve a still-long-off industry goal of safe fully automated vehicle operation.

And had 2020 gone differently — say, without a devastating pandemic to muck things up — the Summer Olympics in Tokyo would have been a venue for demonstrating the progress the institute has made at its Ottawa Lake facility. Before the Olympics’ postponement, Toyota had planned to give rides in autonomous vehicles at the games in Tokyo’s crowded Odaiba district using technology developed here, as well as in more advanced labs in California and Japan.

The very rural Ottawa Lake facility “provides a place where we could validate all of the features and the capabilities before we are able to test them on public roads, so we could make sure everything is safe,” explained Sharin Shin, senior manager of automated driving field operations with the institute.

The Toyota testing area opened in October 2018 on a piece of what was once a 320-acre test facility owned by drivetrain automotive supplier Dana Corp. Located in the middle grounds of a 2-mile concrete track, it consists of a large asphalt pad dotted with painted intermodal shipping containers and portable traffic lights. Infinitely configurable based on the simplicity of its design, the facility “is a kind of engineers’ sandbox,” Shin said. Another piece of the former Dana property is used as a marshaling yard by Fiat Chrysler Automobiles to ship Jeeps and other vehicles around the country.

Surrounded by large earthen berms, test roadways and intersections have been painted on the asphalt to simulate real-world conditions, said Erin McColl, a mechatronics engineer who is a senior technical program manager in the driving division at the institute.

Half of the asphalt “is U.S.-specification roads, and the other half is Japanese-specification roads, so this is a facility where we can take our vehicles, and actually running the same code on both sides of the track, see how we perform with this sort of global idea of, how do we apply automated driving in different driving environments?” McColl said. The surrounding oval test track is equipped to allow engineers to simulate highway on- and off-ramps as well.

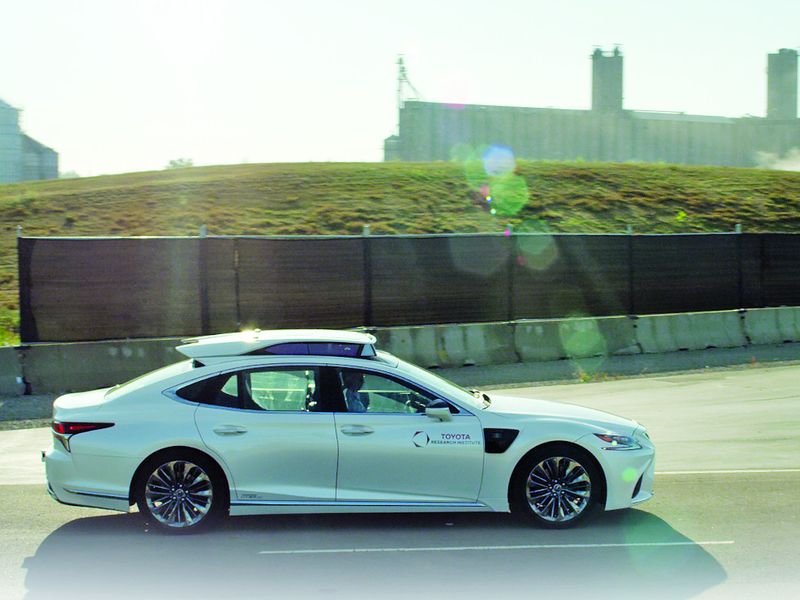

Toyota is developing a pair of automated driving technologies. One, called Guardian, works in concert with the driver to enhance their capabilities, like an involved personal driving coach, allowing the driver to operate the vehicle in a safer manner and automatically intervening when safety requires. The other, Chauffeur, is focused on full autonomy, where the human driver can be replaced, depending on the terrain.

Level 4 Chauffeur-equipped vehicles were going to be on display in Tokyo during the Olympics.

In Ottawa Lake, stacked shipping containers “replicate like sightline occlusions, and [they’re] able to block our sensors, so we’re able to test that in a closed-course environment,” Shin said.

While Toyota uses the Ottawa Lake facility for some testing, it also does on-road testing of its automated driving systems in nearby Ann Arbor, Mich., in California and elsewhere. Together, it’s a system of testing and verifying that makes sure the technology is safe and performing as expected, McColl said.

By the time “we go to public roads, we’ve had massive amounts of broad-based testing and simulation, and we’ve verified that everything does what we want it to do,” McColl explained. “So now when we’re on the public roads, we have high confidence in the capabilities of our vehicles.”