As auto and truck manufacturers invest heavily in hydrogen fuel cell transport, they are considering another alternative — hydrogen combustion engines that can replace diesel motors in a broad array of vehicles.

It’s not an entirely new idea. Swiss inventor Francois Isaac de Rivaz built a combustion engine powered by hydrogen and oxygen in 1806.

More than 200 years later, Toyota and Cummins are taking another look. BMW dabbled with it more than a decade ago but abandoned the technology to push into battery-electric cars and plug-in hybrids.

Among major automakers, Toyota may be the lone company seriously exploring hydrogen internal combustion engine car development now. It has prototyped a hydrogen combustion Corolla, and Toyota Motor Corp. President Akio Toyoda drove a hydrogen combustion GR Corolla hatchback in a 24-hour endurance race at Fuji Speedway this year.

Toyoda has said he believes there are many ways to reduce carbon emissions, and hydrogen combustion engines, which emit nitrogen oxides but not CO2, may have a role in transportation.

Truck and heavy-duty vehicle manufacturers also are looking at hydrogen internal combustion engines as a substitute for diesel vehicles in some settings.

“A hydrogen internal combustion engine shares very similar performance and efficiency attributes to a diesel internal combustion engine,” said Jim Nebergall, general manager of hydrogen engines at Cummins. “This means it’s a suitable replacement for any diesel application.”

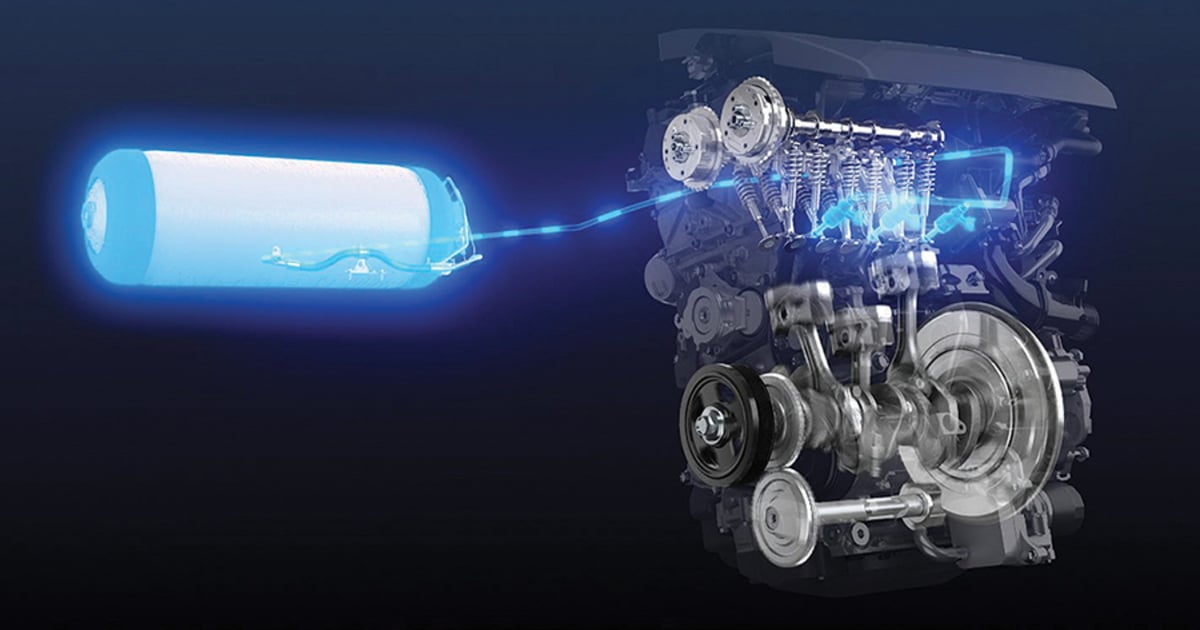

Like other combustion engines it burns a fuel to turn pistons. That’s different from a fuel cell, which employs membrane electrodes that use hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity that powers electric motors. Most diesel and gasoline mechanics would understand how to repair a hydrogen combustion engine, but working on fuel cell vehicles requires significant training.

Cummins is betting on a developing market for heavy-duty vehicles using hydrogen combustion engines.

It unveiled a 15-liter hydrogen engine at the Alternative Clean Transportation Expo in Long Beach, Calif., in May. The powerplant is based on what Cummins calls a fuel-agnostic platform. The engine’s components below the head gasket are similar. But above the head gasket, there are different components for different fuel types.

Cummins plans to put the engine into production in 2027. In September, Werner Enterprises, a large trucking company, signed a letter of intent to purchase 500 Cummins’ hydrogen internal-combustion engines upon availability. The trucking company sees the engine as a tool to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. It will work with Cummins to test and validate the engine.

But the engine’s use as a form of green transport depends on the broader availability of clean hydrogen. The market and infrastructure for clean hydrogen are in their infancy.

On the roster of zero-carbon transportations — battery electric, hydrogen fuel cell, hydrogen internal combustion engine — “the hydrogen internal combustion engine stands out because of its low initial cost, familiarity, proven combustion durability, robustness to harsh environments, and performance in challenging duty cycles,” Nebergall said.

He sees applications for farming, construction and port operations. It also would work for long-haul and regional-haul trucking; vocational vehicles such as dump trucks, cement mixers and snowplows; and emergency vehicles such as firetrucks.

The companies that build those vehicles are eyeing the technology but also keeping a view of how regulations might develop for clean transportation.

“We are continuing to invest in the combustion engine, and we are looking to see if we can use hydrogen in that application as well,” said Jessica Sandström, senior vice president, global product management at Volvo Trucks.

“One of the uncertainties, of course, is the political decisions regarding zero emission,” Sandström said. “Is it zero CO2 or is it zero emission, full stop? If you have a combustion engine, even with hydrogen, you will get very small emissions coming out, nitrogen oxide.”

Daimler Truck Group’s Detroit family of diesel engines can run on hydrogen, said Martin Daum, Daimler Truck CEO.

“If we see a market coming, we can pull it off the pre-development stage and put it into a full-fledged project,” Daum told Automotive News.

The truck company is waiting “because all the signals from regulators in Europe and California are to ban combustion entirely,” Daum said.

But there’s likely to be room in the market for hydrogen combustion engines somewhere, and their compatibility with diesel engines is an advantage, said Daniel Sperling, founding director of the University of California, Davis, Institute of Transportation Studies and a member of the California Air Resources Board.

“Just because Europe and California want something, that doesn’t mean that’s the whole market,” Sperling said.

Still, he’s skeptical the industry will deploy hydrogen combustion widely.

“A fuel cell is much more efficient than combustion. You use less energy. You then don’t have the cost of expensive tanks on the vehicle. You don’t have the NOx emissions,” Sperling said.

“No one knows how this will play out, and we are all trying to figure it out.”