When will BEVs reach the tipping point and overtake the internal combustion engine as the power source of choice? This is already agreed by most as the defining question of the modern Automotive era.

Some industry analysts claim that retail price parity will mark such a tipping point. However, this is just one factor required for there to be a mass change in consumer behavior in favor of BEVs.

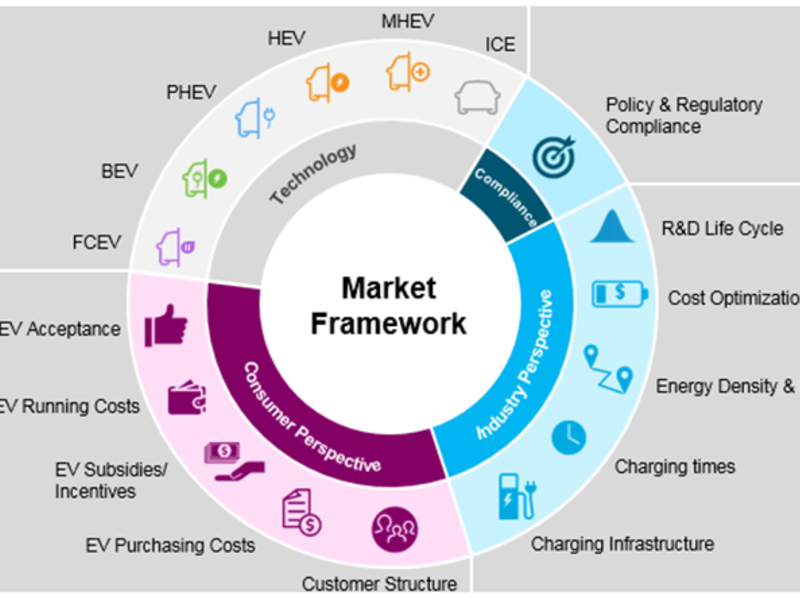

Perhaps the question we should be asking is: ‘When will the four key elements that make up the entire market framework achieve parity, driving consumers to choose BEVs over ICEs?’ Each of the four key driving forces is affected by a number of variables, often highly regionalized, and a complex matrix in which vehicle price is only one part of the equation. Charging infrastructure and regulatory frameworks will have to align. Total cost of ownership, reliability, and convenience models will have to improve along with regulatory and legislative change, before any tipping point occurs.

The cost of the battery in a Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) currently represents a significant proportion of the overall vehicle cost. If we select the Nissan Leaf in the UK as an example, the base trim 40kWh 2019 model has a manufacturer suggested retail price (MSRP) of USD40,000 prior to subsidies. It’s impossible to know precisely how much Nissan is paying for the 40kWh pack, but our 2019 industry average estimate would be in the range of USD250/kWh. Which allocates USD10,000 of the overall vehicle cost then for the pack. That’s 25% of the MSRP attributable to the pack. According to powertrain experts from IHS Markit, if the entire cost of the powertrain is factored in—including motors, power electronics and software —then a figure of around 35% of total MSRP of the UK specification Leaf is attributable to the ‘Powertrain’.

Regionalities aside, these costs have resulted in BEVs being priced at considerably higher levels than traditional internal combustion engines (ICE), despite the relative simplicity of the battery/motor powertrain in comparison to a modern ICE. However, this scenario is fluid and changing and as battery technology evolves and capacity to produce increases, the cost per kWh to the point at which a BEV hits pricing parity with ICE technology is closing.

Yet whether parity is the factor preventing the wholesale shift to BEVs is questionable even today and also remains highly dependent on regional market factors. After taking into account the many different government subsidies, parity can have a significant impact when integrated into a wider set of supportive policy, such as in the Norwegian market. In the UK, where Renault markets a B-segment Clio and Zoe at close to parity (after £5k government subsidy) the Clio still far outsells the Zoe BEV by 10 to 1 (Clio 20k units, versus Zoe 2k units sold in calendar year 2018) which shows that with the current technology paradigm and infrastructure provision, the longstanding objections of range anxiety, and ease of charging remain significant obstacles in consumers’ minds.

Equally important to outright costs is the ‘convenience factor’ and ease of use. Changing consumer behavior by requiring an apparent step-back in convenience requires a psychology shift. This we feel, is more profound than overcoming the pricing hurdle. So even if total cost of ownership (TCO) and range objections can be fully countered, asking the end vehicle user to alter their behavior in order to accommodate a re-charge time to full range of over 10 minutes means there is still work to do.

Regardless of the issue of parity, there remain several significant hurdles to the wholesale take up of BEVs of which infrastructure provision remains the biggest. The rise in urban living throws up serious challenges to BEVs in the high-density areas of the city. Personal ownership of vehicles in city centers is traditionally low, but living in an apartment and owning a BEV in the city makes ownership challenging at best and simply not feasible at worst. Car sharing schemes utilizing BEVs still require dedicated charging points and space to be found for them. Electric taxis and ride hailing services present greater feasibility, but both businesses focus in detail on cost per km, vehicle longevity/reliability and time in service to remain competitive. Again, a pure BEV might still struggle to make a convincing argument.

The fossil fuel distribution model, where a supplier ensures you have ample access to the product is not being matched in terms of BEV charging infrastructure. We are witnessing even in relatively BEV friendly markets such as the UK, a combination of ad-hoc government infrastructure, coupled with manufacturer and power supply company initiatives that are slowly creating a network which remains patchy.

The lack of universal EV charging networks is perhaps one of the biggest practical hurdles in terms of the ‘tipping point’. The average consumer is not particularly interested in working out and planning which charging network they will and won’t be able to use when they finally make that EV purchase.

Once pricing parity is achieved, there is a growing belief that cost of BEVs will continue to fall, or that car makers will continue to lower MSRPs of BEVs based on the cost of the power source. This does not bare much relation to the actual practice of manufacturers over time and ignores the need to build margin into the price of BEVs, partly to recoup sunk costs in the technology, and because shareholder behavior is not geared to support an acceleration of BEV parc at the expense of profitability. Indeed, there is a strong likelihood that BEVs could represent a larger profit opportunity than ICE, again based on the simplicity of the components. So the pricing floor—the point at which an OEM will experience margin erosion if breached—seems destined to be relatively high.

The most powerful instrument that can be wielded in terms of accelerating BEV availability is the regulatory framework. Many Western European governments such as France and the UK are already articulating a ban on ICE vehicles from 2040.

However, it should also be noted that any administration that bans ICE vehicles and forces consumers towards BEVs without significant subsidy or proper infrastructure is likely to face a considerable challenge. The impact of the regulatory environment obviously differs from region to region and is a significant driving force in this equation.

To illustrate this point, IHS Markit data forecasts light vehicle market share for PEV in Europe (a combination of plug-in hybrid (PHEV) and BEV) at 9.3% by 2021, rising four-fold to 40% by 2031. Whereas in the United States, we forecast PEVs to take 5.2% in 2021, again rising four-fold, but only capturing 20% of the light duty market by 2031. Furthermore, in the EU28 countries with increasingly stringent CO2 regulatory frameworks, and in China, where its New Energy Vehicle (NEV) policy compels OEMs operating in the country to manufacture EVs in the country, the regulatory pressure is hugely influential and will have a marked effect on reaching any tipping point regarding BEV take up. However, the United States (by which here we mean outside California and sec 177 states) is currently the obvious exception. Fuel economy regulations are not conducive to encouraging BEV demand, fuel remains cheap by international standards and associated political will remains largely absent.

Finally, it also not a ‘binary’ situation where it is merely traditional ICE technology versus BEV in terms of the current technology paradigm. OEMs have more tools at their disposal in terms of meeting the more stringent emissions environment that will evolve in Europe, in particular, over the next decade. ICE based solutions, such as petrol/electric hybrids in the many various forms, provide many of the gains without many of the drawbacks of BEVs. If pricing parity were the only consideration, then BEVs may well become the powertrain source of choice, but factor in any or all of the above and the argument becomes nuanced and less clear.

The point at which a battery can match ICE for cost parity is forecast to be in the range of USD100 to USD80 per (kWh). This assumption, combined with assumptions on energy density improvement, will then put the OEM in a position to install a 100kWh battery pack, provide total system power of between 250 and 300 hp and offer in the region of 500 miles of range.

This combination of cost, range and performance will herald the mass adoption of the BEV, reaching parity to an equivalent diesel while also moving considerably closer to the cost of an equivalent gasoline option. IHS Markit holds the view, as indicated in the above forecast, that it may take until 2030 for this example to apply to all passenger car segments, with larger vehicles (less dependent on energy density advancements due to having more room), likely to reach this point earlier. In the interim period, PEV market share is forecast to make up over a third of all new vehicles sold in Europe, but only a fifth in the United States. Significant – yes, but there is no imminent wholesale shift, or ‘tipping point’, anticipated in the next decade, rather a gradual adoption as the other key elements align to make PEVs a realistic and preferential choice for the consumer.

About IHS Markit (www.ihsmarkit.com)

IHS Markit (NYSE: INFO) is a world leader in critical information, analytics and solutions for the major industries and markets that drive economies worldwide. The company delivers next-generation information, analytics and solutions to customers in business, finance and government, improving their operational efficiency and providing deep insights that lead to well-informed, confident decisions. IHS Markit has more than 50,000 business and government customers, including 80 percent of the Fortune Global 500 and the world’s leading financial institutions. Headquartered in London, IHS Markit is committed to sustainable, profitable growth.

Automotive offerings and expertise at IHS Markit span every major market and the entire automotive value chain—from product planning to marketing, sales and the aftermarket. For additional information, please visit www.ihsmarkit.com/automotive or email [email protected]

IHS Markit is a registered trademark of IHS Markit Ltd. and/or its affiliates. All other company and product names may be trademarks of their respective owners © 2019 IHS Markit Ltd. All rights reserved.