HOCKENHEIM, Germany — The most carbon-intensive part of producing an electric vehicle is manufacturing the battery that goes in it. It’s a task that accounts for about 40 percent of the emissions associated with building, for instance, a Porsche Taycan.

To reduce those emissions, Porsche is targeting the battery-making process from multiple angles — requiring suppliers to use renewable power, sourcing raw materials regionally and developing battery chemistries that are more energy efficient.

For Porsche, the mission is urgent.

The German sports car maker has set a goal of being carbon neutral by 2030, spurred by tightening emissions regulations primarily in Europe and China. To get there, it is electrifying its lineup, starting with the four-door Taycan fastback. Next year, Porsche will launch a battery-powered version of its bestselling Macan compact crossover. Looking ahead, Porsche expects to electrify its Boxster roadster and midsize Cayenne crossover.

Almost half of the carbon dioxide emissions generated during the life cycle of an EV are produced at the manufacturing stage. Much of those emissions are related to the extraction and processing of raw materials.

Transporting those raw materials — often halfway around the world — to battery factories, and then to vehicle assembly plants, further adds to the emissions footprint.

Porsche said its supply chain is responsible for about 20 percent of the automaker’s total greenhouse gas emissions. This percentage will probably rise to close to 40 percent by 2030 as more production shifts to electrified vehicles.

In response, Porsche is pressuring suppliers to manufacture batteries and other components exclusively with renewable energy. Suppliers unwilling to switch to certified green energy will no longer be considered for contracts in the long term, the automaker said.

A major source of emissions in battery production occurs during the processing of raw materials such as nickel and cobalt. The associated smelting and purification processes are extremely energy-intensive, said Benjamin Passenberg, Porsche senior manager of high-voltage system concepts.

“It’s very important to have green energy, especially in cell production, where you need a lot of energy to heat things,” Passenberg told Automotive News at a media event here.

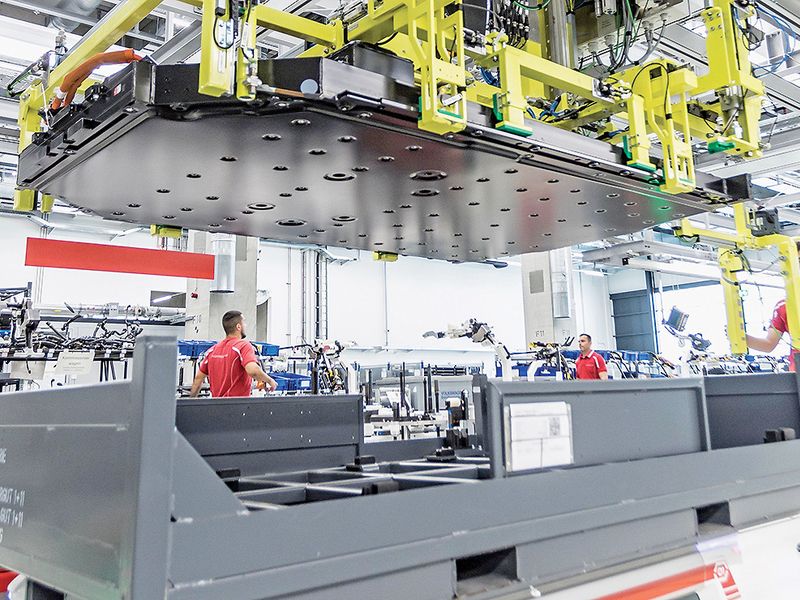

Porsche is leading by example. The automaker said it will invest more than $1.1 billion in decarbonization measures over the next decade, including reducing assembly plant CO2 emissions. Taycan production at the Zuffenhausen plant in Stuttgart, for instance, has been carbon neutral since its launch.

But using green power to manufacture batteries won’t be enough by itself for Porsche to reach its ambitious emissions targets. It will require reimagining the battery itself.

To do that, Porsche is developing a battery it says will pack more power, charge faster and have a lighter carbon footprint.

The technology relies on using a greater amount of silicon as the anode material in the lithium ion cell, rather than just the typically used graphite.

Theoretically, silicon anodes have about 10 times higher energy density, said Otmar Bitsche, Porsche’s head of electromobility.

“We expect about 20 to 25 percent more watt-hours per liter compared with conventional lithium ion batteries,” Bitsche said.

Energy-efficient cells mean fewer are needed to power a vehicle, reducing the overall weight and footprint of the battery pack — a critical requirement in an EV.

The new battery’s “pouch” cell design is also environmentally sustainable because it reduces the aluminum housing material compared with a cylindrical cell design. Aluminum production is a major emitter of carbon emissions.

Significantly, the new cell will have less cobalt content than a typical lithium ion cell.

“Cobalt is difficult to source — there are only a few mining sites worldwide and often in countries with questionable human rights,” Passenberg said.

Cobalt accounts for 20 percent of the cathode material in the Taycan battery. Porsche hopes its new technology will shrink the cobalt content to 5 to 10 percent.

To further reduce emissions, Porsche will source cobalt, nickel and other battery raw materials from European locations that are closer to where the new batteries will be made, near Porsche’s Weissach Development Centre. Acquiring cathode materials from Schwarzheide, Germany, rather than China, for example, reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 25 percent, Bitsche said.

Porsche hopes to commercialize the high-performance battery by late 2024 or early 2025. The goal for the planned production plant is to reach a minimum annual capacity of 100 megawatt-hours — enough to supply 1,000 vehicles.

The initial application will be in motorsports, where a premium is placed on high-performance and fast-charging capabilities.

“We typically need another two to three years to do the transfer to series production cars,” Bitsche said. “So you will see it in production cars in the second half of the decade.”