Mining companies are going to great lengths to source the raw materials needed for electric vehicle batteries, even miles below the ocean’s surface.

They are racing to tap into these seabed stockpiles, striking deals, developing mining processes and equipment and striving to be eco-friendly.

Meanwhile, environmental groups want to slow the rush until more is known about the impact on this largely untouched area of the Earth. Several automakers have joined a moratorium on sourcing metals from seabed mining.

Vast fields of rocks containing high concentrations of nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese needed for EV batteries cover what’s known as the abyssal plains. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the area makes up 70 percent of the ocean floor and is located at depths of over 10,000 feet. It is the largest habitat on Earth.

The pebble- to potato-size rocks coating the seabed, called polymetallic nodules, contain vastly more nickel and cobalt than land reserves. Terrestrial mining of these materials is burdened by dependence on China, environmental impact and child labor use in Africa.

There are 274 million metric tons of nickel within a 1.7-million-square-mile area of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, according to a 2020 Nature report based on U.S. Geological Survey data. USGS said that compares with 95 million metric tons of existing known land reserves. There are 44 million metric tons of cobalt on the seafloor compared with 7.5 million on land.

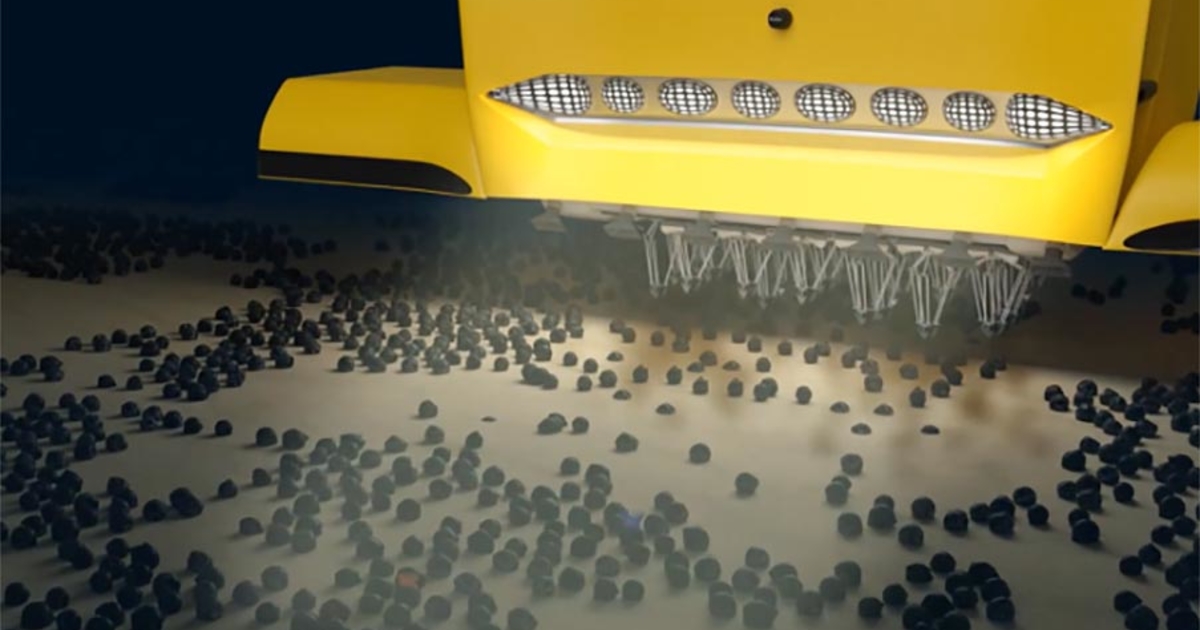

The acceleration of EV sales and soaring demand for battery materials have triggered an underwater gold rush. Mining companies are developing technologies such as tractor-size vacuums and autonomous robots to collect polymetallic nodules.

Obtaining tons of rocks from 2 miles or more below the sea surface may seem like a complex and costly process, but “much of the equipment proposed is borrowed straight from the offshore oil and gas playbook,” Ed Freeman, managing editor of Ocean News & Technology, told Automotive News.

It’s difficult to compare the economics of seabed with terrestrial mining because there are so many variables, said Frik Els, editor of Mining.com. Seabed mining hasn’t yet taken place at scale, he said.

One expected advantage is that the process includes loading ore onto ships. That saves steps in the supply chain. Cobalt, for example, gets mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo and then sent to South Africa, where it is shipped to China for processing. The metal then goes to battery factories in Europe and the U.S.

“If the mine is 1,000 miles from the nearest port, you have to ship millions of tons via rail,” Els said. “If you’re at sea, you just drop it into the hold and take it to customers.”

Most companies are targeting the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located between Mexico and Hawaii. Its proximity to the North American market and location “in friendly waters” makes it attractive, Els said.

Overseeing this potential bonanza is the International Seabed Authority, established in 1994 under the 1982 United Nations Convention’s Law of the Sea. It includes nearly 200 member countries. The authority administers an area approximately half the size of the world’s oceans and since 2001 has awarded 19 exploration permits to a variety of international companies.

It is developing a mining code that outlines “regulations to govern the exploitation of mineral resources” on the seabed. In the meantime, mining companies and environmental groups are prepping for a faceoff.

As mining companies develop equipment, conduct tests and work with ocean researchers to assess environmental implications, others are marshaling opposition. The World Wildlife Fund last year called for a moratorium on seabed mining to allow for an assessment of whether it can be done without harming the ocean.

BMW, Volkswagen, Volvo, Google and Samsung signed the moratorium and pledged not to source seabed minerals. Other groups, such as Greenpeace and Pew Charitable Trusts, have called for halting seabed mining until the environmental impact is understood. Pacific Island nations Fiji, Samoa and Vanuatu have voiced opposition to seabed mining, and Chile asked for a 15-year pause to study the impact.

But there are parties that are actively supporting seabed mining because of its economic potential. The Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority awarded three exploration permits to mining companies this year. The Pacific Island nation of Nauru plans to apply to the International Seabed Authority to allow commercial extraction of polymetallic nodules starting in 2023.

This month, Metals Co. of Vancouver, British Columbia, said it successfully tested, with the international authority’s recommendation, collecting polymetallic nodules from the seafloor in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Working with Swiss offshore contractor Allseas, the company used large vacuums and a 2-mile pipe to transport 15 tons of nodules to a ship.

Metals Co. subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources Inc., sponsored by Nauru, plans to submit the test results to the authority for regulatory and permit processing.

Proponents of seafloor mining argue it is less problematic given the location of the resources on land and their associated environmental, geopolitical and labor issues. But environmental groups say there’s little data on seafloor mining to understand the implications for ocean ecosystems.

“Any deep seabed mining ultimately removes both species and habitat,” Jessica Battle, senior global ocean governance and policy expert for the World Wildlife Fund-Sweden, told Automotive News.

The fund proposes innovation and battery recycling to fill the gap for needed materials.

“This is where investments need to go rather than opening up yet another extractive frontier in a sensitive environment,” Battle said.

Several European automakers and Samsung won’t use seabed materials.

“Volkswagen Group consulted multiple experts from the public sector, academia and business and conducted a thorough analysis of available data on deep-sea mining,” the automaker said via email. “Our conclusion is that current research cannot sufficiently rule out adverse impacts of mining and tailings disposal on the delicate deep-sea ecosystem.”

BMW told Reuters last year that sourcing battery materials from deep-sea mining is “not an option” because of unknown environmental risks.

But other automakers believe it might have potential.

General Motors “is committed to taking a science-based and data-driven evaluation of the environmental footprint of alternate value chains, including terrestrial and undersea mining,” a spokesperson said. “We continue to follow the developments of multiple parties, including some of our key strategic suppliers, around deep seabed mining.”

The USGS is studying the effects of mining to help the International Seabed Authority determine what environmental protections are needed.

“It’s important to realize that all types of mining have environmental consequences,” said USGS spokesman Alex Demas.

The USGS is in the very early stages of researching these factors, Demas said.

Last month, a group of Massachusetts Institute of Technology ocean scientists released the results of a study on sediment clouds created by seabed mining. They worked with Global Sea Mineral Resources, a Belgian marine engineering company exploring ways to extract polymetallic nodules.

The MIT researchers equipped what they called a “pre-prototype collector” with instruments and cameras to monitor the sediment plume created by the machine. Their measurements showed that as the sediment plume dispersed, it “remained relatively low, staying within 2 meters of the seafloor,” an MIT publication said.

“The big takeaway is that there are complex processes … that take place when you do this kind of collection,” said Thomas Peacock, an MIT mechanical engineering professor and co-author of the study.

In general, researchers are concerned the plumes could spread beyond the mining site and harm deep-sea life.

Most mining companies applying for Seabed Authority permits use machinery like the collector in the study, which suck rocks and surrounding material from the seafloor.

The Global Sea Mineral Resources system separates nodules from sediment inside the collector. The nodules are sent to a surface vessel through a pipe, while most of the sediment is discharged behind the collector.

Metals Co. said its method carries polymetallic nodules to the surface, with water and sediment discharged to a “midwater column.”

Pliant Energy Systems, of New York City, plans to use underwater robots with slowly undulating fins to pick up polymetallic nodules. The company said the robots and other buoyant methods to bring the nodules to the surface are more environmentally friendly than relying on pipes.

Impossible Metals, a Pasadena, Calif., startup, plans to deploy autonomous robots to the seafloor to collect polymetallic nodules.

The robots have mechanical hands to pick up individual nodules and use artificial intelligence to collect rocks of only a certain size, CEO Oliver Gunasekara said. If the rocks are too small or contain significant sea life, they aren’t collected, he said.

“The technology to do this exists,” Freeman, of Ocean News & Technology, said of seabed mining. “Now it’s more a case of consolidating the scientific findings from the many marine survey campaigns and setting a clear path towards stringent regulations.”