DRESDEN, Germany — Hundreds of workers are scurrying through Robert Bosch‘s newly opened microchip factory here now, hurrying to turn out more chips to a world that’s starving for the tiny things.

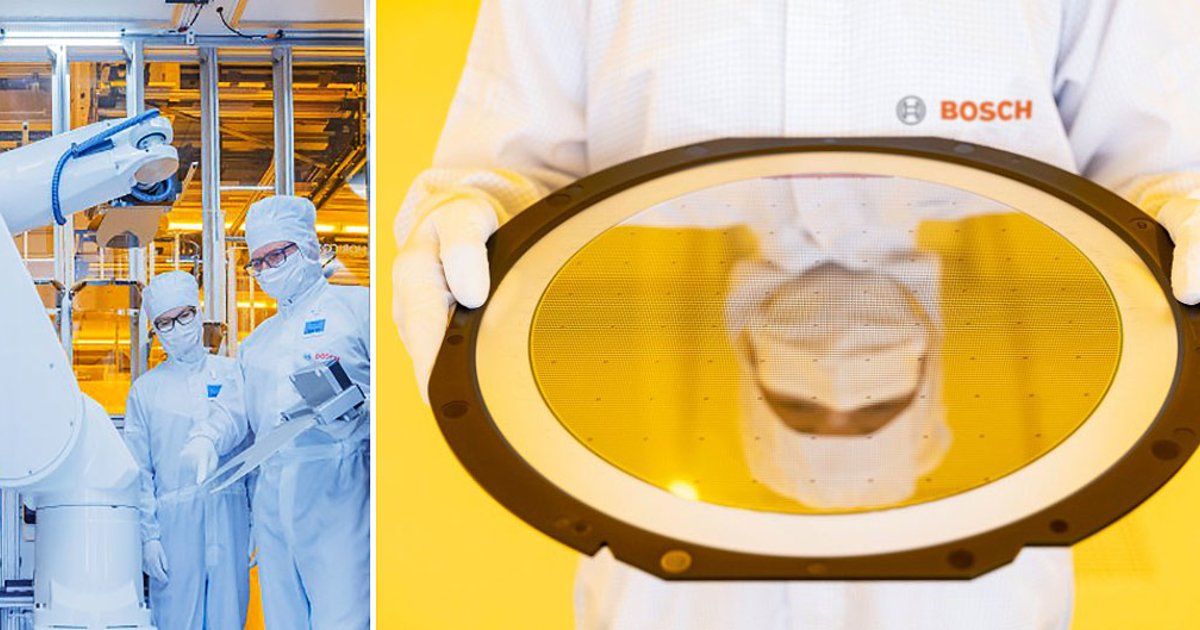

The newly trained employees are wearing hair nets, gloves, lab coats, disposable booties and face masks, all intended to keep every speck of contaminant off every chip. And by year’s end there will be still more workers on the job, working in the eerie yellow light of the new hyper-clean plant that Bosch spent $1 billion to build.

Bosch Chairman Stefan Hartung said operations at Dresden were accelerated to meet the situation.

“They are being ramped up faster than planned, after having started a whole six months earlier than scheduled,” he said at the new line. “Given the supply bottlenecks in our industries, we don’t want to lose any time.”

But the more telling industrial site might be the big dirty vacant lot next door. That’s where Bosch will now turn its attention, with larger plans to spend $3 billion to produce even more chips for an insatiable market.

And Bosch is just one player in what is suddenly a new investment wave.

In response to a catastrophic worldwide chip shortage that has so far knocked more than 13 million vehicles out of production since early 2021, chip producers, including Bosch, and governments, including the U.S. Congress, are pledging unprecedented sums of money into boosting semiconductor capacity — not only to address the shortage but to meet ever larger demand for chips across multiple sectors.

Congress last week passed a bill that will provide more than $52 billion to U.S. companies producing chips and providing tax credits for investing in chip manufacturing.

The European Commission is establishing an investment war chest of more than $45 billion, similar to the U.S. bill just passed.

Large amounts of funding are being committed by individual companies worldwide. More than 90 new wafer fabs or expansions of existing wafer fabs — the industry term for chip fabrication plants — are expected to come online globally over the next four years, according to SEMI, an electronics design and manufacturing industry group.

The scale of those investments is “truly extraordinary,” said Bettina Weiss, chief of staff at SEMI.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. is building a $12 billion fabrication facility in Arizona, one of the largest single investments in the world.

Also in Arizona, U.S. chip giant Intel is investing $20 billion on two new plants. And South Korean conglomerate SK Group said last week it plans to invest $15 billion in its semiconductor business in the U.S., including funding for research and development programs, materials and the creation of an advanced packaging and testing facility, Reuters reported.

Just two weeks ago, the U.S. semiconductor manufacturer SkyWater Technology Inc. of Minnesota said it will invest $1.8 billion for a chip research and production facility in West Lafayette, Ind.

“Even if only half of these facilities come on, we will see a pretty strong capacity expansion for all kinds of semiconductor devices and chips, and the automotive industry will benefit from that,” Weiss said.

Still more investments could be on the way. Ondrej Burkacky, a senior partner with McKinsey & Co. in Munich, said “many companies” are standing by to take full advantage of Congress’ new bipartisan bill that was expected to be signed into law by President Joe Biden.

For an industry that has been rattled by the chip shortage over the past year and a half, the huge new investments are surely welcome news. According to an estimate by AutoForecast Solutions, the lack of chips has forced automakers to cut more than 13 million vehicles out of their production schedules since the start of 2021.

But things won’t get better overnight, for a multitude of reasons.

For one, building a new wafer fab can take up to five years, and automakers need more chips today.

The plants are also incredibly complex to launch. Bosch’s Dresden microchip plant relies on 150,000 sensors to generate 250 megabytes of data every second as wafers are produced there.

Furthermore, a majority of the new capacity investments will go toward leading-edge semiconductor technology — not the less sophisticated chip tech widely used in vehicles. Chip manufacturers are generally prioritizing production of chips used in other industries such as consumer electronics.

Even Bosch, the world’s largest supplier of auto parts, does not plan to funnel all of its semiconductor investment funding toward the chips that automakers need. Bosch has a wide portfolio of other businesses that need chips, such as sophisticated kitchen appliances and power tools.

“As cars become more sophisticated and we move into the era of electrification, chips need to be updated,” said Carla Bailo, CEO of the Center for Automotive Research. “But that’s not going to happen overnight. It will be a gradual shift, because the auto industry has much higher requirements in terms of durability and usage than these other industries.”

The microchip shortage has challenged automakers to attempt to make adjustments on the fly. One of the successes has been Tesla, which has rewritten its software to be able to substitute alternative chips and keep production flowing more freely than many of its rivals.

“How automakers deal with the shortage differs,” said McKinsey’s Burkacky. “A lot of automakers were caught by surprise, and they all struggled in a similar way. Now we’re seeing that the people who can deal better with it have fewer problems.

“Going forward, I think that spread between those that can cope with it and those who cannot is going to grow.”

AutoForecast Solutions reported that in the last week of July, automakers in Europe did not have to cancel any of their weekly production plans because of chip shortages.

Burkacky said the shortage will continue to ease over time, but McKinsey estimated in a June report that supplies could remain strained for three to five more years.

One complicating factor is that demand is not flat: The auto industry’s demand for chips is rising. Electric vehicles and advanced driver assistance features require more chips than traditional vehicles.

Bosch estimates that chips represent about $200 of a vehicle’s value today, on average, but will represent about $800 by the end of the decade.

“Even if you had all the chips you had in 2019, you couldn’t build the same amount of vehicles that you built in 2019 because there are more chips per vehicle,” said Kristin Dziczek, automotive policy adviser with the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. “And we don’t have all the chips yet that we had in 2019.”

But despite its growing demand for more chips, the auto industry is a relatively small consumer of them. The industry currently accounts for less than 10 percent of global semiconductor purchases.

Burkacky believes auto companies would do well to improve their short-term demand planning, sharing information about supply and demand throughout the supply chain with semiconductor manufacturers to leave them better able to keep up with demand.

“They need to have a certain level of courage in their forecasting levels,” he said of automakers and suppliers. “It doesn’t help to only say ‘I’m going to produce X number of cars.’ They need to be clear on which type of cars they’re going to build and what options are going to be there.

“That’s valuable for semiconductor makers, because they are sometimes puzzled by the signals they get from the market. It’s helpful to establish what real demand is.”

Geopolitical and economic risks will also factor into chip sourcing in the near future, experts said.

Much of the world’s semiconductor production comes out of Taiwan, which is experiencing new tensions with China. The New York Times reported last week that the Biden administration is “increasingly anxious” that China could move against Taiwan, though there is no specific intelligence information indicating such a move is imminent.

But at the same time, analog chips are likely to increasingly come from China, Dziczek said. Analog chips, which control mechanical systems in a vehicle, are a technology that “not a lot of companies are investing in” at the moment, she said. And many buyers are reliant on suppliers in China, where trade tensions with the U.S. remain fraught.

“The geographic distribution of where chips are being made is somewhat of an issue,” Dziczek said.

Also of concern: the new possibility of a recession, which could have an impact on automakers’ microchip sourcing plans.

A downturn could at least temporarily ease the problem by reducing demand for new vehicles and making it easier to meet unmet demand.

But Dziczek believes that even in the event of a recession, the demand for vehicles from the retail and fleet markets will keep pressure on chip producers.

In either event, Burkacky warns automakers to assume that a recession-related reduction in demand will be only a fleeting situation and they should not pull back from efforts to improve supply-chain transparency.

“The concern is if people start thinking, ‘OK, there’s hope that the chip shortage will be over faster than I thought, so I don’t need to take any measures on my long-term commitments because all of my problems are going to resolve themselves,’ ” he said.

Instead, he advised, “Assume that any softening in consumer demand is a short-term event and demand will come back. Otherwise we risk being back at the beginning of 2021, caught off guard and running behind on supply.”

Many are encouraged by the steps being taken around the world.

In Germany, Bosch is ready to begin its next investments. They will include expanding capacity at both Dresden and at an older facility in Reutlingen by 2026.

“As early as 2023, we want to extend our Dresden location,” Hartung said. “Among other things, we will add 3,000 square meters of clean-room space, one-third more than at present.

“More chip capacity is one of our objectives.”