Over the past 10 months, Apple has outfitted its latest iPad Pro and iPhone 12 with lidar sensors that enhance the camera capabilities in both devices. Even though the additions have nothing to do with the company’s secretive self-driving vehicle program, the moves nonetheless elicited cheers from one Israeli auto-tech startup.

Opsys Tech has spent the past five years developing a particular kind of lidar for use in driver-assist and self-driving systems called VCSEL, which rhymes with ‘pixel.’ The company’s founders are convinced Vertical Cavity Scanning Emitting Lasers offer advantages over conventional lidar, because they allow more emitters to be packaged on smaller chips and use less power overall.

When Apple started using the same type of lidar, Opsys Tech counted another key advantage — it can further compete on cost.

“By the time Apple finished saying to the world ‘I need VCSELs for my phone,’ everyone was building capacity around the world to supply it,” said Opsys Tech Executive Chairman Eitan Gertel. “Suddenly, the cost went down an order of magnitude. Instead of a dollar or two, it costs pennies. That enables us to use it in automotive, low-cost, high-performance technology.”

Opsys Tech has raised $31 million to date, including an undisclosed investment from Hyundai Motor Corp. The company started delivering its second-generation lidar to Chinese customers in December, he said.

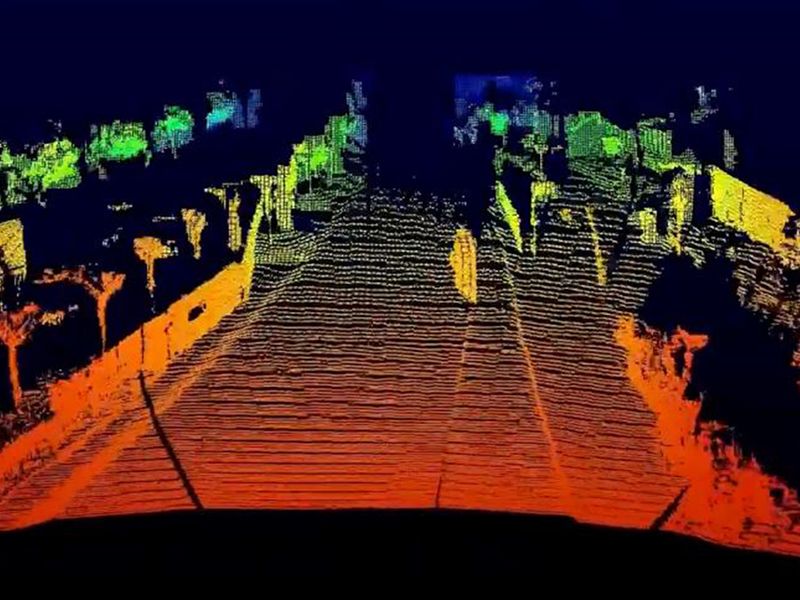

Lidar is used to help cars know precisely where they are in the universe and detect obstacles in their paths. Opsys is not the only provider that’s gravitated toward using VCSEL lasers in its lidar sensors. IBEO and Ouster are two other well-established lidar companies that have incorporated them into their products, according to a November report from Guidehouse Insights.

The report echoed Gertel, noting Apple’s appetite will provide volume in the tens of millions and be a “major contributor” to cost reductions. Guidehouse said VCSEL has limited detection range, but that it is highly accurate, and optimal for use in driver-assist functions such as automated emergency braking. Performance is expected to improve with Apple’s entry.

Opsys and some industry analysts view VCSEL as enabling the lidar industry’s third major iteration. In their early designs , lidar suppliers used mechanical assemblies that had moving parts, which were tolerated for testing but frowned upon for automotive-grade, widespread deployments.

Next came solid-state lidar, which comes in multiple varieties, including flash, which functions akin to a camera. Though not necessarily new, now comes VCSEL, which allows Opsys to pack 2,000 to 3,000 lasers on a wafer and steer the light beams with no moving parts across both horizontal and vertical planes. It also allows the sensors to capture information at rates of 1,000 frames per second, Gertel said, compared with the conventional industry range of 30 to 60 frames per second.

Founded in 2016 by a team of telecom and broadband veterans, Opsys didn’t set out specifically to develop VCSEL. It backed into the approach by eliminating all the other ones while it developed products for both the automotive and defense industries.

“The things we saw out there, we didn’t really like,” said Gertel, formerly CEO at Finisar and vice president at JDS Uniphase, both optical communications tech companies. “We don’t think having lidar is taking a physics lab and putting it in a box on the car. … Solid-state for us means absolutely no moving parts, and flash has limitations on distance and resolution. … This has to be done with lasers that are highly manufacturable with very high yield rates. I know the challenges, because I made lasers around the world, and that’s how we got into VCSEL.

Once it settled on the VCSEL approach, Gertel says the company focused on patenting intellectual property related to the technology.

Opsys’s second-generation sensors could detect objects at 150 meters and Gertel said the upcoming third generation will detect them at 200 meters. For self-driving vehicles traveling at highway speeds, pushing their sights further down the road will be a key to success.

“At the moment, where I think a lot of the value is really in the long-range sensing,” said Tom Jellicoe, an analyst TTP, an independent technology consulting firm based in the U.K. “It’s the classic example of a truck going down the freeway at 70 mph, and there’s a piece of tire debris at 200 meters. It takes a bloody long time to stop a truck, so it needs to make its decisions early.”

Gertel is wary of competitors who boast longer-range capabilities but don’t mention the tradeoffs they need to make, in terms of resolution and reflectivity, to get there.

“What you want to hear and see them say is, ‘We meet all the specs, all the time, under any conditions,” he said. “That’s what we can do.”

Watching five lidar suppliers go public via special-purpose acquisition companies in recent months further leaves Gertel some combination of perplexed and incredulous.

“You are going to go public with no revenue, losing money and promising revenue in five years? Apparently that is the way it goes,” he said. “It is possible to do that. The question is, ‘Are they going to perform to that or not?’ They are raising tons of money, and the fact is that gives you more life. But how many investors are looking at the fundamental technology and not getting caught in the hype? Your judgment is your judgment.”