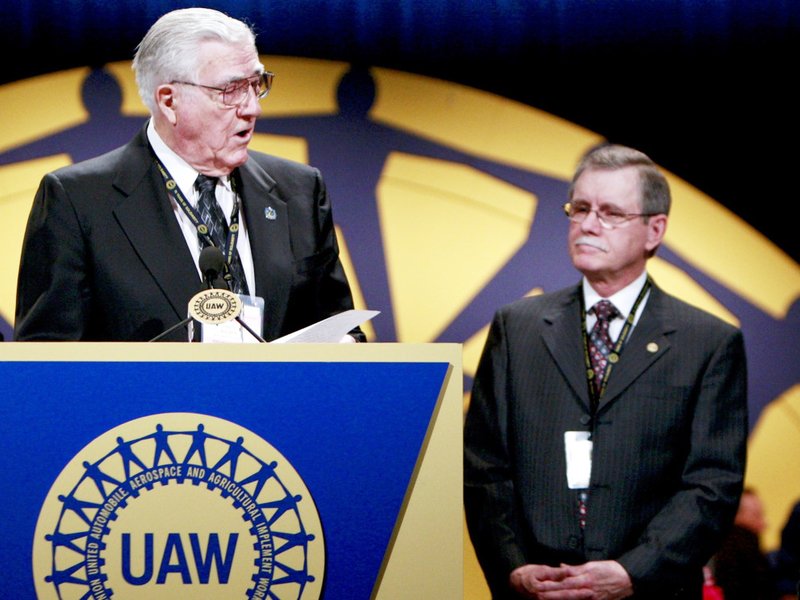

Owen Bieber, who led the UAW in negotiating landmark labor deals that expanded health care coverage and job protections, helping to ease the pain for workers during a turbulent period as Detroit automakers battled economic downturns and the rise of Japanese and European brands, died on Monday, the union said in a statement. He was 90.

Bieber, a tall, quiet man with roots in rural western Michigan, was the last of the UAW’s top leaders to come out of the era of Walter Reuther, the fiery UAW chief who built the union into a powerful social force from 1946 until 1970, when he died in a plane crash.

During Bieber’s tenure steering the UAW, from 1983 to 1995, the union battled job cuts and membership losses as the Detroit 3, notably General Motors, lost market share to Japanese and other automakers.

Under Bieber, the Canadian Auto Workers union split off from the UAW while the union won the establishment of a Jobs Bank program at GM, Ford and Chrysler. Under the Jobs Bank, negotiated during 1984 labor talks with GM, laid off UAW members at the Detroit 3 received the bulk of their pay and benefits despite plant closings.

Over time, the Jobs Bank program was increasingly attacked by union critics as preventing the Detroit 3 from becoming more efficient. Employees assigned to the Jobs Bank performed maintenance work and other tasks. The program didn’t end until 2009, when the union agreed to scrap it as GM and Chrysler sought U.S. government-backed bailouts and Ford struggled under heavy losses.

The Bieber-led UAW was also criticized in the Michael Moore-directed documentary “Roger & Me” in 1989. The film’s primary target was then-GM CEO Roger Smith, who cut jobs in Moore’s hometown of Flint, Mich., and under whose watch GM’s once-dominant share of the U.S. market tumbled. But Moore’s documentary also attacked the UAW for not doing enough to stand up to GM.

Faced with declining membership ranks in the auto and other industrial sectors, Bieber and other UAW officials recruited workers in other industries, notably government, education and health care.

Bieber often said his biggest regret was the union’s failure to organize the thousands of workers at Japanese transplants that first took root in the Midwest in the 1980s. But under his watch, the union secured a pact in 1983 to extend union representation to employees at a jointly owned GM-Toyota assembly plant in Fremont, Calif. And in 1985, the union added some 22,000 state government workers in Michigan.

While Bieber was not afraid to use strikes to secure economic gains, over time, as globalization and automation remade the U.S. factory floor, they delivered less and less for the union.

One ominous walkout came early in Bieber’s tenure as head of the UAW.

During a notably bitter 17-month strike at Caterpillar Inc. in 1994-95, when the heavy equipment producer used replacement workers to keep production lines and profits flowing, workers eventually returned to the shop floor without major gains.

“He was instrumental in guiding the UAW through some of its most challenging times,” Bill Ford, executive chairman of the Ford Motor Co., said. “He was an advocate for the union’s membership and his leadership has had a lasting impact.”

A lifelong progressive champion of social justice, Bieber represented the AFL-CIO in 1986 as part of budding boycott of American companies doing business with South Africa’s apartheid government. In 1984, he and other labor leaders were arrested during an anti-apartheid demonstration outside of the South African embassy in Washington, DC.

“He was not only a devoted trade unionist but a social activist whose impact was felt around the world,” UAW President Rory Gamble said. “Whether it was his support to end apartheid in South Africa or in Poland, Owen stood on the right side of history for the nation and the world.”

Bending wire

Owen Bieber was born on Dec. 28, 1929, in North Dorr, Mich., a farming community near Grand Rapids. His Catholic household featured portraits of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the pope. He joined the union in 1948 as a wire bender at McInerney Spring and Wire Co. in Grand Rapids, the same auto parts factory where his father worked

He was responsible for bending by hand the thick border wire on car seats.

“It was a hard job,” Bieber told The Washington Post in November 1982. “After the first hour in there, I felt like just leaving. If my father hadn’t worked there, too, I probably would have.”

A year later, at age 19, Bieber was elected to his first union position — shop steward — at UAW Local 687.

He started bargaining immediately after securing a steward button, he once told The Detroit News, “because there were grievances to take care of, and that’s part of collective bargaining.”

He worked his way up in various union posts, including president of Local 687, became a regional director and later the union’s vice president in charge of the vast GM department.

The GM bargaining role, covering some 400,000 workers from coast to coast, became especially tough in the early 1980s when Detroit’s automakers faced depressed industry sales and rising foreign competition.

Bieber was forced to help negotiate the first concessions in the history of GM. The company’s workers, coddled for years by some of the most lucrative labor contracts in America, agreed, among other things, to put off annual wage increases and eliminate some paid time off. But the contract was by no means supported unanimously and rank and file workers ratified it by only a slim margin.

“I thought my life was going to get easier [in the GM department],” Bieber, recalling how difficult the negotiating had been at small plants in outstate Michigan and how, until 1982, bargaining at GM had always been lucrative for the union, told the Associated Press. “All of a sudden the bottom fell out and I got my baptism of fire.”

Bieber succeeded Douglas Fraser as UAW president in 1983, becoming the seventh leader of the Detroit-based union.

“It’s not that Owen bowled anybody over with his charisma,” a UAW executive board member told The Detroit News after the board nominated Bieber for the union’s top post. “He isn’t charismatic. But he also didn’t offend anybody. I think we’d all agree that he’s a good Christian gentleman who has integrity and can be trusted.”

Colleagues often described Bieber as warm, compassionate, steady, deliberate, and a nuts-and-bolts man.

“Owen Bieber will be remembered for his commitment to workers and his leadership of the UAW through challenging times for more than a decade,” GM said in a statement.

In 1991, Bieber and the UAW suffered a setback when the CAW broke away to become an independent union over disagreements about negotiating priorities. (The CAW later merged with another Canadian union to become Unifor.)

Over time, as Japan’s automakers opened more U.S. plants, the UAW was forced to adopt more collaborative work rules with management as the Detroit 3 battled to improve productivity and efficiency.

The UAW, under Bieber, sought to demonstrate it could work with Detroit automakers while resisting job cuts. The union agreed to a special labor contract with GM’s new Saturn Corp. unit at a new Spring Hill, Tenn., factory. That accord would be ended after Bieber left office.

Throughout the 1980s, Bieber and top UAW officials also faced opposition by New Directions, a group within the union that said leadership wasn’t tough enough with Detroit’s automakers.

Under Bieber’s watch, the UAW’s membership continue to drop steadily from a peak of 1.5 million in 1979. GM alone eliminated 54,000 jobs and closed 21 plants in the early and mid 1990s.

The UAW had to scramble to prevent civil wars among locals as GM sought concessions by pitting U.S. plants against each other, with limited success.

“Whether you look at wages, health care, etc., our members have done far better than most have. We were able to defend the standard of living,” Bieber said in May 1995, a month before he retired as UAW president. “Thank God, we had the foresight to put in training programs. Now, we have the best and most far-reaching training programs in the world.”

In 1991, Chrysler, aiming to “improve efficiency” and reduce expenses, eliminated five seats from its board, including one held by Bieber, ending the nation’s most prominent experiment in putting labor in the corporate boardroom. The seat was first held by UAW President Douglas Fraser as part of Chrysler’s 1979-80 bailout by the federal government.

Bieber didn’t run for re-election after reaching the union’s retirement age of 65. He was succeeded by Stephen Yokich in 1995.

Some “don’t realize what it was like before the unions,” Bieber said in a Sept. 2011 interview with Michigan’s MLive.com. “When you walked through the door, you had to unclothe yourself of rights.”