Henrik Fisker knows there’s plenty of baggage leftover from his first attempt at building a car, the Fisker Karma gasoline-electric luxury sedan, a decade ago.

Investors got burned. Jobs promised at a former General Motors plant in Delaware never materialized. Worse, the 2,450 or so cars that were built had more problems than a calculus textbook.

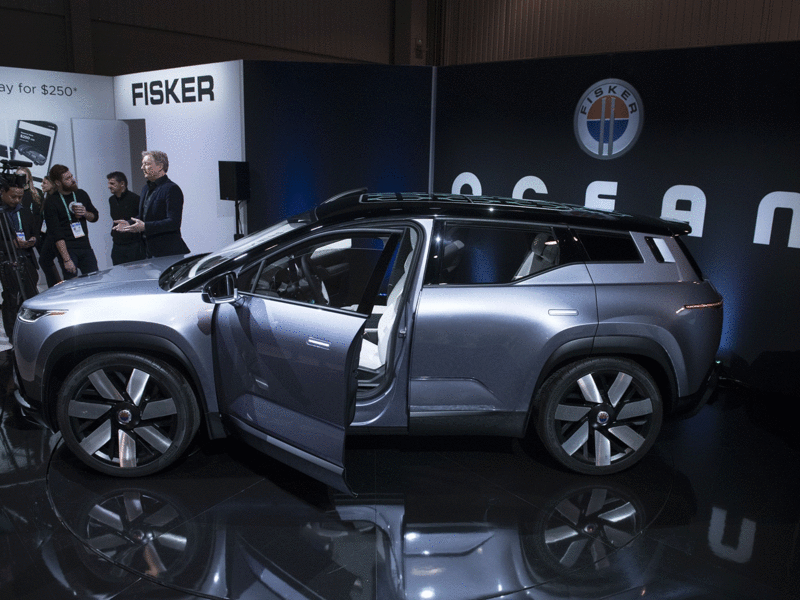

One chance is usually all anyone gets at starting a car company. But Fisker is getting another a shot. He’s a raised a billion dollars through a special purpose acquisition company, or reverse merger, and he’s signed a production contract with Canadian supplier Magna that will see the $37,499 Fisker Ocean electric crossover debut in the fourth quarter of next year, if the project remains on track.

I recently chatted with Fisker, now 57, for a half hour on a Zoom call — he ensconced in his sunny, airy Los Angeles headquarters, me in Detroit in full view of GM’s giant downtown headquarters.

Although the Karma is far in Henrik Fisker’s personal rearview mirror, its stylish specter still casts a large shadow over his current project. Fisker knows he’s got to deliver a world-class vehicle right out of the box. He knows he’s not going to get a third chance if the Ocean sinks.

Perhaps the biggest lesson from the Karma debacle, Fisker told me, involves money.

“We learned to raise enough money for your entire first program, to get it to market, because you never know when the [money] market is going to be closed. This time, we really decided that when we were ready, we needed to raise at least $1 billion, which we did.”

Constantly pitching investors and waiting on funding badly impacted every aspect of the development of the Karma, he said.

“You saw, with both Tesla and Fisker, at the time it was always stop-go, stop-go,” he said. “And that is detrimental to the team, adds costs to the project and annoys investors because you are late.”

Another lesson: Bad quality will doom a startup.

Unlike Fisker’s deal with Valmet Automotive, which built the Karma in Finland, Magna, Fisker says, is taking responsibility for much of the Ocean’s product development. Magna, he says, will be sourcing and testing many of the parts used to assemble the Ocean. To keep costs down, Fisker said the Ocean will be made with as many off-the-shelf components from Tier 1 suppliers as possible.

Having Magna build the Ocean frees Fisker fiscally from having to find or build his own plant, and from dealing with purchasing, manufacturing equipment, work force training, logistics and all else that goes in to manufacturing an automobile.

“I don’t think it is a good idea to build your own plant as a startup company and try to teach people how to build a car, especially a car that is brand new with new technology. That is why we chose Magna as a partner. They are in charge of quality. It’s not us. They have to deliver a quality car at the end of the line. We’ll check, and if the quality is not there, they will take it back and fix it. That’s on their plate,” Fisker said. “Magna is building Mercedes, BMWs and Toyotas; they will use the same people, same methods and same processes, and I am absolutely convinced we will have a very high-quality car.”

Fisker equates his role as CEO and chief designer to that of a Hollywood producer.

“Compared to a movie, the Karma was an indie movie shot somewhere in Africa with little electricity,” he said. “And this one is being shot right in Hollywood with the right equipment.”

Fisker is determined that the Ocean will not have the same ending as the Karma.

The failure of his first company was a tough pill to swallow for a man who knew nothing but success in his earlier years as head of design for Aston Martin and for the now-classic BMW Z8 roadster he designed for the German automaker.

“When Fisker Automotive ended the first time, I felt like I was out of luck more than anyone else,” Fisker told me. “It was liked getting a double knockout, lying on the floor and thinking you are never going to get up again.”

“You know, it has been 10 years of hard work to get back. And those 10 years taught me a lot of lessons. I am definitely feeling humble about it. And feeling humble about people who are willing to invest in my experience and who feel I have some talent in designing and making a car,” Fisker said. “I truly understand somebody spending their hard-earned money to buy our stock. I am humbled and honored by that. That actually makes me quite emotional.”

From what I can tell, one of the last people who had a second shot at starting his own car company also had the initials H.F. His name: Henry Ford.