There’s a right way and a wrong way to retire as an auto industry executive.

The right way is to relax and enjoy the blue sky and a few golf courses. The other way is to do what Johan de Nysschen is doing — which is to say, he’s back at work.

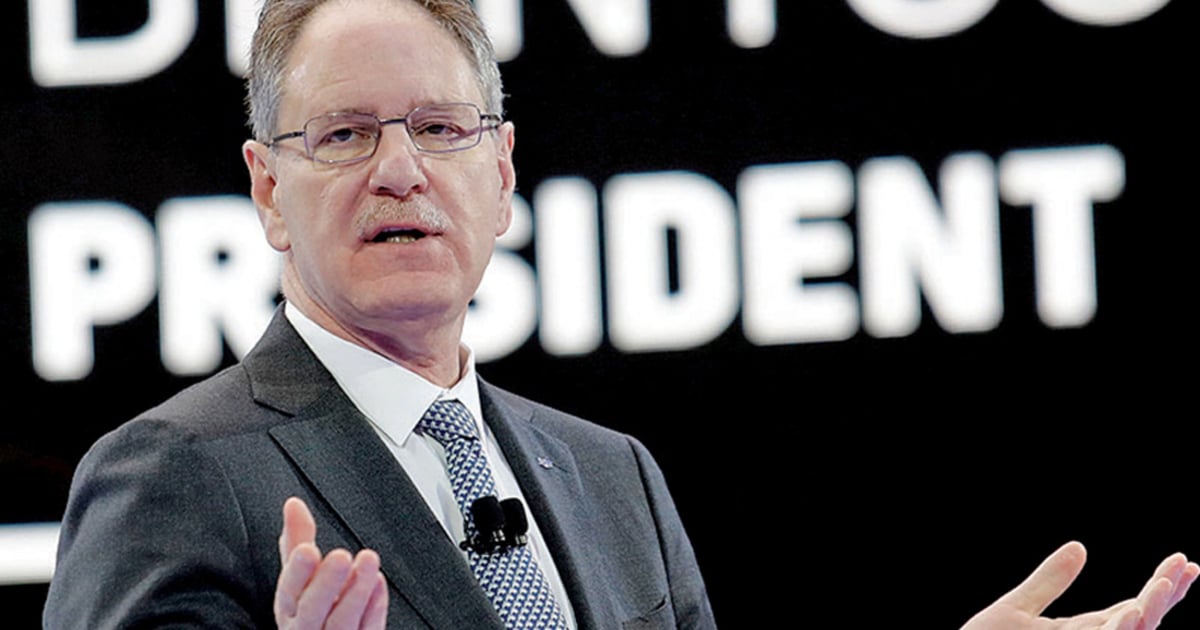

At 63, de Nysschen’s career has consisted of:

- Being president of Audi of America, where he doubled sales in eight years.

- Running the North American operations of Infiniti, where he shook up the brand by changing the names of its products.

- Working as executive vice president of General Motors and running Cadillac, where he relocated the Detroit brand’s headquarters to Manhattan (GM moved it back as soon as he was out the door).

- Working as North American COO at Volkswagen of America, where he locked horns with the company’s German supervisory leadership by pushing them to enlarge VW’s U.S. footprint.

He thought he had reached his finish line. But not so.

Since retiring from Volkswagen last year, de Nysschen fell into first one new career in Chattanooga, the midsize Southern river town where VW recruited him and his wife Anna to come live in 2019, and then into a second one. And now, a third.

The South Africa native was named chairman of the Chattanooga Area Regional Transportation Authority, his new hometown’s transit service. It sounds like a far cry from the auto industry, but there is a connection, in de Nysschen’s view. In this new job, he hopes to improve access to public mobility — not merely for the convenience of Chattanoogans, but as one element of an even bigger task he’s working on — helping the city boost the size of its available work force for automotive expansion or any other economic expansion.

In his post-retirement new career No. 2, de Nysschen serves as “special adviser” to a local action group called Chattanooga 2.0. Its mission is to find ways to lift thousands of people in the city’s surrounding county out of poverty and into the work force. More than 45,000 residents of Hamilton County are below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“People here told me that it has been this way for 40 years, despite efforts to break through the poverty,” de Nysschen said. “I encountered this problem while at Volkswagen, when I was responsible for manufacturing in the U.S. and Mexico, and we recruited a third shift here in Chattanooga. But I suppose I’m known for being somewhat blunt, and I’ve told the noble people who are engaged in this effort with me that we need to stop concerning ourselves with the people who don’t want to work and to instead find the ones who do and help them.

“If we can get just 10 percent of the people who are locked in this trap of poverty to just escape the hold it has on them, that’s 10 percent progress. And I think it’s doable.”

That undertaking is uniting community leaders, educators, business executives and the chamber of commerce to come together to address issues of education, daycare services, the high school curriculum, vocational training and public transportation to bring more of the population into the work force pool.

“When we set out to have a third shift at Chattanooga,” said de Nysschen, “I got pushback from the Germans, who said, ‘You don’t have enough labor there. Where will you find all the workers?’

“And you know, that’s partially true. But Chattanooga is a microcosm for all of America, because all of America is tight on labor supply right now. So I wanted to address that.”

As if all that weren’t enough, the supposedly retired executive now has been pulled back to work for a vehicle tech startup, Propitious Technologies LLC.

Propitious announced this month that de Nysschen has become CEO of the Phoenix company, “responsible for articulating the vision of Propitious’ patent-pending emissions reduction technology, architecting the product rollout plan, securing funds to fuel company growth, and negotiating with potential acquisition partners.”

De Nysschen describes the new technology as a green alternative to the big diesel generators that keep the nation’s fleet of some half-million refrigerated trucks cold. In a nutshell, it works by capturing kinetic energy. As a truck rumbles down the highway, a power-generating suspension system mated to an electric generator produces the power for refrigeration. A secondary compact battery-storage unit can store enough of the charge to keep working when the truck is parked at night for the driver to sleep.

In other words, it is an electric power plant that gets its juice from the normal rumbling and bouncing and jostling that takes place on the road, harvesting the energy produced by the slight up and down movement of the trailer on the suspension.

De Nysschen said he’s enthusiastic for the technology because it’s green, replacing what is largely unregulated diesel emissions with a device that works through what he calls “undulating mass.”

The same kind of emissions reduction might be achieved through a large battery, he acknowledged. But it would need to be about four tons worth of battery costing some $200,000.

De Nysschen estimates the Propitious system will come in at about 1,800 pounds and cost about $20,000.

“It’s a massively compelling opportunity,” he said. “It was enough to bring me out of retirement, and I find it incredibly energizing and intellectually stimulating.

“I don’t have time to play golf.”