The Federal Reserve slashed interest rates by half a percentage point in the first such emergency move since the 2008 financial crisis, amid mounting concern that the coronavirus outbreak threatens to stall the record U.S. economic expansion.

The rate cut, which came between the central bank’s regularly scheduled meetings, was announced hours after Group of Seven finance chiefs held a rare teleconference to pledge they’d do all they can to combat the fast-moving health crisis.

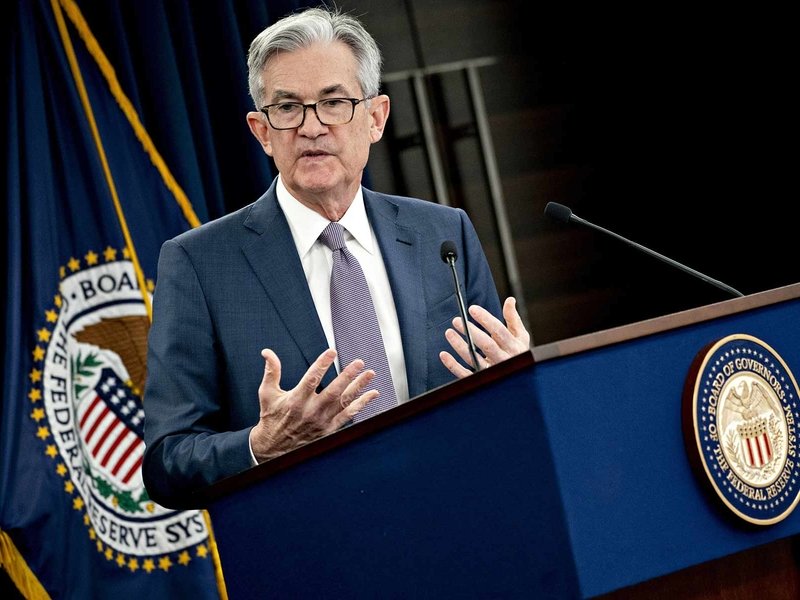

“My colleagues and I took this action to help the U.S. economy keep strong in the face of new risks to the economic outlook,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell told a hastily convened press conference in Washington on Tuesday. “The spread of the coronavirus has brought new challenges and risks.”

Powell left the door open to further action by the central bank at its next scheduled meeting March 17-18. “In the weeks and months ahead we will continue to closely monitor developments,” he said.

The rate cut could provide additional support for new-vehicle sales, though analysts say the immediate impact will be minor and that the move was designed to lower any risks the coronavirus would trigger a recession.

In February, the average interest rate on a new-vehicle loan was 5.6 percent and remained under 6 percent for the eighth month in a row, according to Edmunds.

The Fed chief acknowledged that the Fed doesn’t have all the answers, adding that it would take a multi-faceted response from governments, health care professionals, central bankers and others to stem the human and economic damage.

“We do recognize a rate cut will not reduce the rate of infection, it won’t fix a broken supply chain. We get that,” Powell said. “But we do believe that our action will provide a meaningful boost to the economy.”

Auto impact

Overall, analysts expect new-vehicle sales to slide this year as economic growth slows and rising prices force consumers to consider used cars.

The Federal Reserve’s decision Tuesday to make an emergency cut in interest rates could also support new-vehicle sales, though analysts say the immediate impact will be minor and that the move was designed to lower any risk the coronavirus would trigger a recession.

Jonathan Smoke, chief economist at Cox Automotive, said the Fed’s move came as a surprise to economists. He’s skeptical the cut will deliver lower interest rates to most car shoppers. Instead, he said the lower cost of funds will allow lenders to take on higher risk spreads.

“If we don’t see rates come down, there won’t be a boost to new-vehicle demand from this cut,” Smoke said.

Jessica Caldwell, executive director of insights at Edmunds, said rate cuts generally boost sales, especially in an environment where high transaction prices are a drag on volume.

The Fed’s 2019 rate cuts prompted the average interest rate to fall below 6 percent for the eighth consecutive month in February.

“It’s not going to get people who were not going to buy a car to buy a car, but for the people that were on the fence, this type of news puts them over the edge of buying versus waiting,” Caldwell said.

The growing threat posed by the coronavirus, however, will likely offset the goodwill of the rate cut in the near term.

“People don’t really want to venture out to places they don’t have to at this point. People tend not to make big purchases,” Caldwell said, saying fears of the outbreak were at a fevered pitch.

“The auto industry is not immune to these developments,” she added

The bigger concern for new-vehicle sales will be any disruptions to global supply chains, Smoke said, as automakers idle plants because of government travel restrictions and other steps needed to contain the outbreak.

The impact the coronavirus will have on dealership sales remains to be seen, though Cox and Edmunds project increased closures, quarantines, and travel restrictions could not only lower sales, but likely trigger a recession.

The Fed votes

The vote for the rate cut to a range of 1 percent to 1.25 percent was unanimous even though the Fed said in a statement that the “fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong.” Powell has staked his chairmanship on sustaining the U.S. economic expansion, now in its record 11th year.

“The Fed has very little ammunition and the ammunition that it does have is not at all suited to the task of managing a potentially large adverse supply shock,” said Jonathan Wright, economics professor at Johns Hopkins University and a former Fed economist. “They have taken the view that they should do what they can with the tools that they have.”

G-7 coordination

The Fed’s decision could presage a wave of easing from other central banks around the world although those in the euro-area and Japan have less scope to follow with rates already in negative territory.

The Fed move also followed public pressure for a cut by President Donald Trump, whose stewardship of the economy is central to his reelection campaign this year.

After today’s shift he called for more, demanding in a tweet that the Fed “must further ease and, most importantly, come into line with other countries/competitors. We are not playing on a level field. Not fair to USA.”

Tuesday was the first time the Fed had cut rates by more than 25 basis points since 2008 and the reduction marks a stark shift for Powell and his colleagues. They had previously projected no change in rates during 2020, remaining on the sidelines during the election year, after lowering their benchmark three times in 2019.

In a public health emergency, lower rates do little for factories lacking needed materials from abroad and are unlikely to spur consumers to shop or travel if they’re scared of infection. But they should support consumer and business sentiment as well as ease financial conditions by making debt payments easier to manage and by calming market volatility.

Lawmakers are also working on a $7.5 billion virus response bill, another reminder that critical fiscal policy can take weeks to move through Congress.

One lesson Fed officials will take away from this moment is how rapidly their policy space is used up in a crisis.

Total cuts of one percentage point this year, which several Wall Street firms are forecasting, would bring the bottom range of the Fed policy rate down to 0.5 percent. If the virus impact is worse than expected, or if the economy is hit by a separate shock, the policy rate could strike zero.

At that point, Fed officials are left with unconventional tools, such as purchases of longer-dated Treasuries — known as quantitative easing. The effectiveness of such tools when longer-term rates are already low remains to be seen.

The Fed is in the midst of a review of its tool kit to achieve its goal of maximum employment and stable prices. They are considering policies such as outcome-based forward guidance, where a policy change would be linked to some tangible metric such as achieving an inflation rate, and yield curve caps.

Jackie Charniga and David Phillips contributed to this report.